When you visit a cocktail bar, chances are you’ve either encountered a few of the local legends or someone trained/influenced by one. Recently, I got to sit down at the Silvertone with one of Boston’s most well-known legends, Brother Cleve, and he regaled me with stories of his own entry into craft cocktail-dom as well as a history of Boston’s part in bringing the craft cocktail back to life.

If you want, sip on an Americano cocktail, like we did, as I share with you some of Brother Cleve’s and Boston’s story:

LOREN BORNSTEIN: Thanks again for meeting with me, Brother Cleve.

BROTHER CLEVE: Thanks for having me.

L: Let’s just get right to it. So, what makes Boston stand out compared to other cities?

B: The aspect of hospitality here really is something that has been in the forefront with people, for instance, steering guests toward other bars. “Have you been here or here or even here?” There’s a famous story where Jackson Cannon had some guests at The Hawthorne who were getting ready to go to Drink and Jackson texted John Gertsen—who was then General Manager of Drink—saying I have two guests who are coming over and told him what they had been drinking with him. So, Jackson calls them an Uber and sends them over and John has drinks already made for them and a reserved sign waiting.

L: Seems that, even if bars are competitive, there’s a lot of camaraderie. I imagine the size of Boston has a lot to do with it. It’s not the size of New York City.

B: Everybody knows each other in the cocktail bar scene. I mean, it’s expanded from when I kickstarted it 25 years ago. [we both laugh] It’s still fairly small. Everybody’s kinda friends with each other and hangs at each other’s bars.

You don’t see it in New York, because it’s fucking a lot harder. It’s also kind of true in San Francisco and LA. So, that’s been one of the things here. Boston was an early practitioner’s city, and part of that is well…because of me. [more laughter] I hate to sound like a douchebag.

L: [laughs] You don’t. Not at all. I mean, look at all the articles and interviews surrounding you and your influence. It’s the truth. You are a huge part of the reason behind the Boston and national cocktail renaissance.

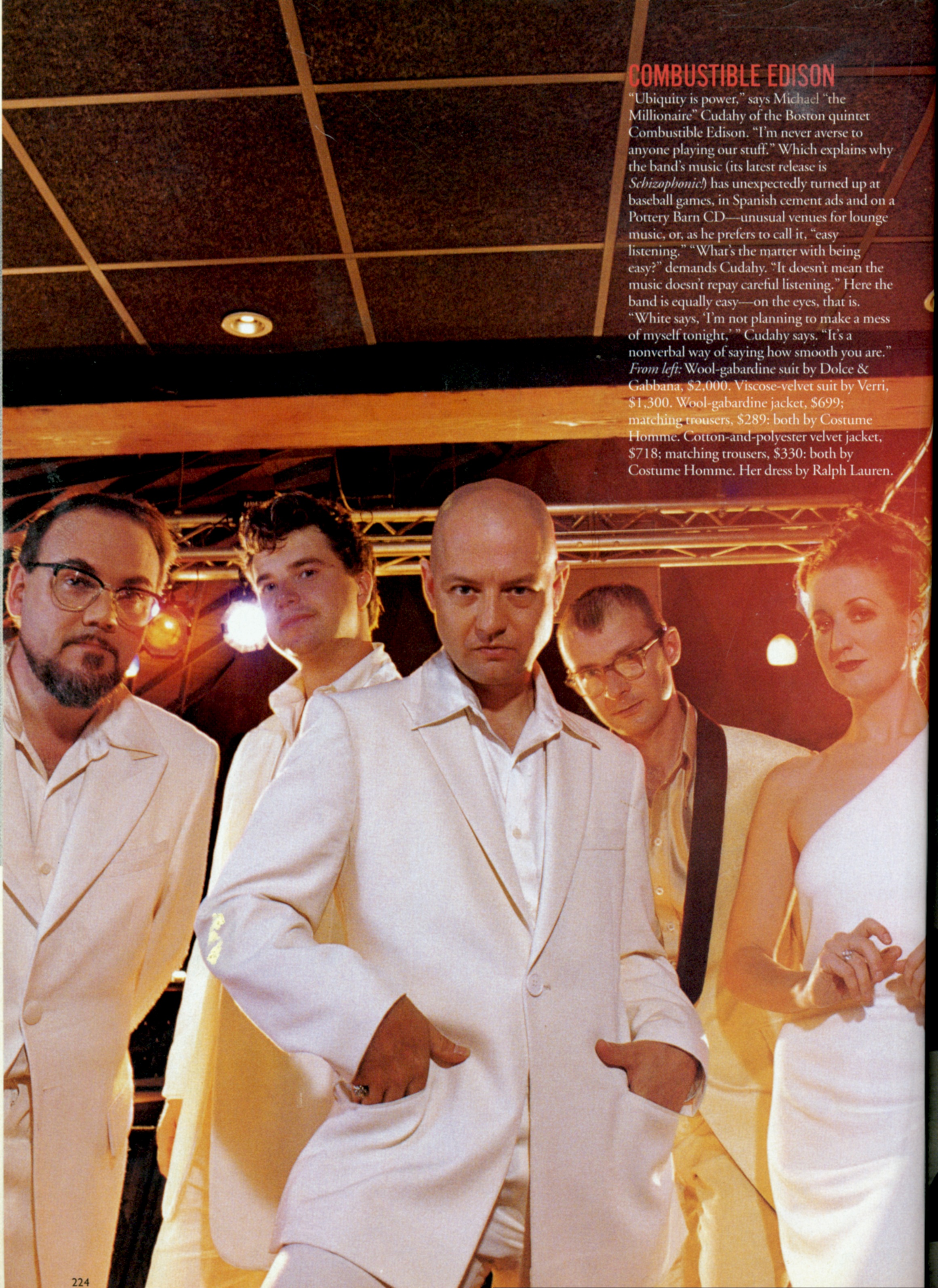

B: [laughs] Thanks. Well, part of it is because I was part of the first, maybe we were the only, cocktail band: Combustible Edison. We played lounge music. We had our own cocktail: the Combustible Edison, and we had a Campari sponsorship out of that. It was brandy, Campari, and lemon juice shaken and served up.

L: Double-strained? [cracking up]

B: [laughing as well] Those didn’t exist at the time.

So, the recipe was on the back cover of our CD’s. Before we had our sponsorship, Campari was confused—this was before they knew about our cocktail—and would ask, “Why did we just sell 20 cases in Madison, WI?” And it’s because we played a show in that area.

Our booking agent at the time was also booking Sonic Youth, Nirvana, and other grunge bands. And we come out at those same venues in our matching outfits, a vibraphone, and doing old Martin Denny stuff and our originals, and we drank cocktails on stage.

So, a lot of these venues would start having the, “Buy a ticket and you get a free Combustible Edison cocktail.” It became such a thing that Campari got in touch with us and we got a sponsorship.

My other band, The Del Fuegos, actually did the first rock beer commercial too. Miller paid us $150,000 to drink their beer on stage.

L: [laughing again] I’m sorry, what? Yes! That is excellent. I’d drink Miller for $150,000. That’s amazing. I’ll have to see if I can find this commercial.

B: It was like six cases of Miller delivered a night backstage. Every once and awhile, the Miller rep would find us with Bud backstage and we’d get in trouble. [laughs]

L: You have an amazing reputation for music and cocktails. So, how did you—I’ve read your story multiple times—become Boston’s person? Was that something you wanted to do for yourself or did someone just approach you like, “Yo, we know fucking nothin’, and we need help.”

B: It was actually through the music. I always drank cocktails. My grandmother gave me my first cocktail, a Manhattan, when I was 8 or 9, right around the corner in fact, at Warmouth’s. It’s long gone. But, as a young punk rocker, I was always drinking Manhattan’s or Old Fashioned‘s.

L: Made the right way or?

B: Oh no, no no no. They were made, a Manhattan back then would’ve been Canadian whiskey, and if there was any vermouth at all, it might be a splash of both to make it a Perfect Manhattan, and with the Martini & Rossi that had been on the rail for 4 years. [more laughter and ughs]

But, y’know, we had no idea we were supposed to refrigerate vermouth.

L: And the Old Fashioned with the muddled fruit like a cherry and orange or a lemon?

B: Yep. And some sugar at the bottom that would be crunchy and you know, an ounce and a half of something like Crown Royal or CC (Canadian Club) or VO (Seagram’s VO).

“I think it’s the conviviality that sets [us] apart. We’re the shadow of New York, but we’ve been a very innovative town with food and beverage.” – Brother Cleve

L: How do you think it went from the classic recipes, which are not those, to that, and how did we come back from that?

B: Part of it has to do with the second World War, there was no whiskey after Prohibition. To make whiskey appear magically, they would blend whiskey with grain spirit (vodka), blended whiskey was basically the only thing you could get in America in the 40’s, 50’s, and 60’s with some exceptions. Rye went out of fashion with Prohibition. It was considered the alcoholic’s drink. If you’ve ever seen the movie The Lost Weekend, sophisticated people did not drink rye.

During WWII, there was a ban on alcohol production, because everything went to making product for wars. America’s taste changed with the introduction to vodka after we allied with Russia. As we absorbed different cultures abroad, it became introduced into our country, and Hollywood particularly was behind some of the trends. You have the Red Scare and drinking vodka was a way to say “fuck you” to McCarthy and his congressional committee. The Hollywood elite would drink it while the government questioned them.

L: Seem like Hollywood influence really has played quite the part in our cocktail world: James Bond and the Vesper cocktail immediately comes to mind. This is really enlightening. Coming back to the original question, how did cocktails go from their classic to the (often bad) versions and come full circle?

B: So, in the 50’s, things became lighter and sweeter. Bacardi seized on this by changing the formula of its rum to be lighter, to compete with vodka. You start getting Harvey Wallbangers, White Russians, Bailey’s and Kahlua are introduced, and, of course, drugs. The hippies weren’t exactly embracing the drinks of “the man”, even though the punks were.

L: It makes sense. So, we spent a few decades saying “screw you” to “the man”, but, really, we were just drinking poorly put together drinks that were extremely high in sugar and chemical product. That’s unfortunate. That’s a lot of time in the industry where people aren’t learning proper technique, history, or just knowing what is quality product. I feel like this has been an issue in all aspects of food and beverage, especially during this time period.

B: It was definitely what was going on for a while.

Then, you have the 80’s and the cocktail renaissance starts slowly. In Boston, it starts with the B-Side Lounge in 1998. Silvertone opened in 1999. It probably also saw a start after the Boston Globe did an article on me back in 1996 that I was the “Cocktail and Music guy”.

L: It seems like the startup tech industry started right about the same time as the cocktail renaissance. Especially since B-Side Lounge is where Google started.

B: This is also when I met Misty Kalkofen, who was then bartending at Lizard Lounge, and Jackson Cannon was an assistant booking agent there. (Misty Kalkofen and Jackson Cannon are also behind Boston’s cocktail renaissance.)

There was this weekly party called Saturnalia, which I wrote the cocktail menu for. But, I DJ’ed, and then the Boston Phoenix did an article about it, and, that Thursday night, we had a line around the block, so then the Globe and the Herald did a story. The next thing you know, it’s packed every night for the next couple of years. The guys at Landsdowne St. said we gotta get in on this and asked me to bring the show to another bar, so I started doing it in both places.

And Boston was where I met Patrick Sullivan who came in one night while I was DJ’ing and came to the booth and said, “You probably don’t remember me, but I was the bartender at your 40th birthday party and you taught me how to make all these cocktails, because I’d never made them before. Well, guess what, I’m going to open a cocktail bar. Can I hire you for music and to be a cocktail consultant?” And that was the B-Side Lounge—two years before it opened.

At the B-Side, our first thing was doing Manhattan’s with rye. There were only three ryes available at the time: Wild Turkey, Old Overholt, and Jim Beam Rye. The bottom of the menu would say, “Try a Manhattan made with Old Overholt rye.” And people would ask, “What’s rye?” And we would explain rye and the history of the cocktail…and still make it with the vermouth in the rail, because we still didn’t know we were supposed to refrigerate the vermouth. [laughs]

Speaking of the tech industry and launching the cocktail world into popularity, The B-Side was over on Windsor St. We were right by Kendall Square area, and the entire tech startup world was based in that area. They were ready for us, why? Because of Wired magazine and Paul Harrington’s cocktail column.

L: And my how it has expanded now.

B: It is incredible to see what has happened these past 25 years.

L: I heard a rumor that the post-shift shot of Fernet Branca also originated here, at this very bar (Silvertone) in fact.

B: So, Fernet Branca as a shot started in San Francisco with Garrett Harker. Started at North Beach after a shift. The old school Italian guys would be drinking it, so they started doing it—around 2000. Then he went to work at No. 9 in Boston and came to Silvertone after his shift with the crew and got them to order Fernet. So, around 2001 and 2002, it all started.

L: And my shift shot will now and forever taste of menthol and death. [laughs] Eh, it’s not for everyone. I’ll be okay with Becherovka. Cheers to everyone who loves Fernet.

So, Boston is one of the biggies where craft cocktails started. It’s fascinating how craft cocktail culture is also tied into the startup tech industry boom and why we still see such large crowds at bars after the end of the 9-5 work day. But craft cocktails and cocktail bars weren’t originally part of what made Boston’s drinking culture. What, to you, was Boston’s drinking scene before that?

B: The dive bar. The dive bar was a place that your father, and his father, and his father went before you. Whitey’s in Southie for instance. JJ Foley’s. Oftentimes, you were more frightened outside of the dive bar than inside. But, I lived in South Boston in the early 80’s and it was a very, very different place than it is today. And dive bars aren’t a thing anymore. Dive bars died to real estate. Actually, for Thirst Boston, I’m doing a walking tour of downtown where all of the great dive bars, tiki bars, lobster restaurants, gay bars, where all of them used to be. It was a big part of what made older Boston and really was what Boston was built on.

L: It’s interesting to see the change of the industries, the rise of tech and finance in place of familiarity and mom-and-pop. It is a thing.

We have seen a real loss of culture in many walks of life. It’s a big issue. I do so much work with the LGBTQ community. For instance, the Castro is not what it used to be. I’ve seen so many gay bars shutter and “gayborhoods” disappear. Ethnic areas erased. While all of our cocktail bars are incredible and a delight to have and honor cocktail history, they also come with the cost of the modern age.

B: It is sad in a way. I was just talking about this with Kelly (Coggins), president of the Boston Bartender’s Guild. We were talking about how sad that is that there are, well, no more gay bars and very few actual dive bars. Boston used to be all dive bars. Now, you see expensive condos, schools.

Actually, a couple of years ago, Barbara Lynch had this event where she flew in a bunch of the top bartenders from all over the country, and we all ended up at Doyle’s. 16 of us ended up at Doyle’s in a battalion of cabs and drank pretty much all of the Irish whiskey in the place. But, we had to take them to Drinking Fountain, one of the last remaining dives, and we just had a fantastic time. David Wondrich put it on his “Best Bars in America”. And it is a wonderful place. A beer and a shot.

L: So, that is what makes a dive bar a dive bar? A beer and a shot and a comfortable setting? What about a cocktail?

B: Well, they can likely make you a decent cocktail.

L: I imagine the whiskey selection is a bit better these days. Not just Crown Royal and 4-year vermouth anymore. [I wink and we both laugh.]

B: Yeah, and bitters too. You could say things have changed a little bit.

L: My last question, Brother. What would you say defines Boston now?

B: Now? I think it’s the conviviality that sets it apart.

We’re the shadow of New York, but we’ve been a very innovative town with food and beverage. Probably because it is smaller and because we have a high tech industry here. Also, the amount of universities.

People are looking for things outside of their comfort zone. And also for comfort, if that makes sense? Being welcome and feeling comfortable enough in that feeling to try something new.

L: Brother, it’s been a pleasure. Thank you so much. The places you’ve worked at and people you’ve worked with: It says how much you have been part of the cocktail culture here and the history behind it.

B: Thank you. I’m sure we’ll see each other soon again.

And two weeks later, I ran into Brother Cleve at Tavern Road. Because, of course.

Be sure to check out Thirst Boston April 28-30 and go on Brother Cleve’s tour. Also maybe drink a little bit too.